Obviously I read a lot of anthropology. It’s a topic near and dear to my heart. Some anthropological works are really good (these I try to share with you here.) Others are drek. (Sometimes I share these, too–but in the spirit of, “Ew, this tastes really weird… Here, try some!” Goodness only knows why people do that.)

In my opinion, anthropology has two main purposes:

- To document human cultures, with priority given to those at greatest risk of disappearing

- To make human cultures mutually understandable.

I’m reminded here of the response Napoleon Chagnon gave when asked what the Yanomamo thought he was doing, studying their tribe:

“They arrived at their own conclusion, which I thought was very logical: I’m trying to learn how to become human.” –Napoleon Chagnon

So let’s add #3: Learn what it means to be human.

Some anthropologists specialize in #1. Others are talented at #2. A few can do both. Collectively, the enterprise might get us to #3.

For example, many anthropologists have amassed reams of data on kinship structures, marriage taboos, food/wealth distribution, economic systems (eg hunter-gathering, pastoralism, etc.) If you want to know whether the average milch pastoralist thinks cousin marriage is a good idea, an anthropologist probably has the answer. That’s task #1.

But information doesn’t do much good if it just molders away in some dusty back room of a university library, and the average person doesn’t want to read an anthropologist’s field notes. This is where good writing comes in–crafting an enjoyable, accessible ethnography, like Kabloona, which gives the average reader some insight into another culture. That’s task #2.

Anthropology isn’t supposed to be politicized, but in practice it’s difficult not to get sucked into politics. Anthropologists generally become quite fond of the people they’ve studied and lived with for years. Since they prioritize cultures in danger of disappearing, they end up with both practical and sentimental reasons to side against the more powerful groups in the area–no anthropologist wants to see the people he just spent a decade living with starve to death because a mining company moved into the area and dug up their banana farms.

As a result, the anthropologist often becomes a liaison between the people he studies and the broader world he wants to protect them from.

Additionally, like the quantum physicist, the anthropologist changes the society he studies merely by being present in it. He is an outsider, a person with his own ideas about morality, violence, gender relations, education, money, etc., and moreover, entirely alien to the local economic and social system. He cannot simply slip, unnoticed, into village life without disrupting it in some way–this is the existential problem of anthropology, but since it cannot be solved, (and the wider culture has no qualms about disrupting native life in far larger and more damaging ways, like bulldozing it,) as a practical matter it must simply be laid aside.

One thing anthropologists tend not to do is look very closely at the negatives of the societies they study, such as disease, infant mortality, drug abuse, or violence. After all, who wants to produce a book that boils down to, “I studied these people, and they were brutish, nasty, and unpleasant”?

Let’s compare for a moment two classic works: Elizabeth Thomas’s The Harmless People, whose very title lays out her assertion that the Bushmen are less violent and less capable of killing people than other, more technologically advanced peoples; and Chagnon’s Yanomamo: The Fierce People.

Chagnon actually bothered to calculate how many murders his subjects committed, and discovered that the Yanomamo have murder rates much higher than modern first-world nations. For his efforts he has been thoroughly condemned and attacked by his own profession:

When Chagnon began publishing his observations, some cultural anthropologists who could not accept an evolutionary basis for human behavior refused to believe them. Chagnon became perhaps the most famous American anthropologist since Margaret Mead—and the most controversial. He was attacked in a scathing popular book, whose central allegation that he helped start a measles epidemic among the Yanomamö was quickly disproven, and the American Anthropological Association condemned him, only to rescind its condemnation after a vote by the membership. Throughout his career Chagnon insisted on an evidence-based scientific approach to anthropology, even as his professional association dithered over whether it really is a scientific organization.

Thomas does not bother to offer numerical proof of her claims that Bushmen are more peaceful than other groups, but anyone with a mind for numbers can look at the murders she does report, divide by the number of Bushmen, and conclude that homicide rates are most likely higher in Bushman society than ours.

Of course, Thomas has not been castigated and condemned by the AAA for asserting that first world societies are more homicidal than third-world hunter-gatherers without proof.

It would be simplistic to assert that Marxists and Freudians produce bad anthropology; I am sure they would have equally negative things to say about people like me. Rather, the dominance of anthropology by adherents of any particular political ideology is problematic.

(Anthropologists also tend not to examine very critically the reasons people might want to change their societies.)

The second big problem with anthropology is that most “primitive” societies have disappeared or are mere remnants of their former selves. 100 years ago, we didn’t know there were people living in the middle of Papua New Guinea (and the folks there, I gather, didn’t know about the rest of us.) There were still cannibals, uncontacted tribes of hunter-gatherers, and igloo-dwelling Eskimo. Atlases still had blank spots marked “unexplored.”

By the time Thomas wrote “The Harmless People,” the Bushmen were disappearing. Indeed, the book’s epilogue, in which a private land owner fences off a watering hole where the Bushmen had formerly drunk in the dry season, leading several tribe members to die of thirst, followed by the remaining tribe members’ removal to a settlement, where all of the vices of alcoholism and violence set in, makes for difficult reading.

What’s a modern anthropologist to do? Sure, you could write an incredibly depressing ethnography on the ways traditional lifestyles are disappearing, or you could write a dissertation on the intersection of hip-hop culture and queer identity. (And you can do that without spending ten years in some third-world village with malaria and no internet.)

The result of all of this is that anthropologists sometimes stick their noses where they don’t belong, for purely political reasons. Take, for example, the American Anthropological Association (them again!)’s statement on race:

In the United States both scholars and the general public have been conditioned to viewing human races as natural and separate divisions within the human species based on visible physical differences.

“Conditioned!” Because there is no evidence that pre-verbal infants notice racial or ethnic differences:

Do babies react differently when they are looking intently at the faces of people of different races?

Psychologist Phyllis Katz has cleverly used habituation to try to answer this question. Katz studied looking patterns among 6-month-old infants. She first showed the babies a series of pictures, each of them was shown a person that was of the same race and gender (e.g., four White women). After four pictures, the babies began to habituate to the pictures, and their attention wavered. Next, Katz showed the babies a picture of a person who was of the same gender but of a different race (e.g., a Black woman), or a picture of a person who was of the same race but of a different gender (e.g., a White man). The logic behind the study was that if the infants didn’t register race or gender, they wouldn’t show a different response to these new pictures– that is, they would continue to show habituation. However, if they registered a difference, the babies should dishabituate, and again look with interest at this new stimulus.

The findings clearly showed that the 6-month-olds dishabituated to both race and gender cues—that is, the infants looked longer at new pictures when the pictures were of someone of a different race or gender. But some other interesting findings emerged. Among these was the finding that for both Black and White infants, the infants attended longer to different race faces when they had habitutated to faces that were of their own race.

Back to the AAA:

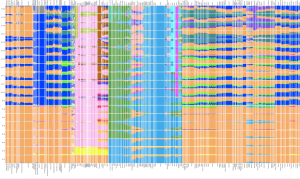

Evidence from the analysis of genetics (e.g., DNA) indicates that most physical variation, about 94%, lies within so-called racial groups. Conventional geographic “racial” groupings differ from one another only in about 6% of their genes. This means that there is greater variation within “racial” groups than between them. In neighboring populations there is much overlapping of genes and their phenotypic (physical) expressions. Throughout history whenever different groups have come into contact, they have interbred. The continued sharing of genetic materials has maintained all of humankind as a single species.

This is dumb. This is really, really dumb. Humans and chimpanzees share 96% of their DNA, but that doesn’t make us the same species. Humans and mice share 92% of our DNA.

Put a dog and a wolf together, and if they don’t kill each other, they’ll breed. Dogs, wolves, dingos, and golden jackals can all interbreed and produce fertile offspring, but we still consider them different species.

I’m not saying human races are actually different species. I’m saying the AAA is full of idiots who parrot popular science articles without understanding the first thing about them. If these are your “scholarly positions,” you don’t fucking deserve your PhDs.

Oh, and by the way, humans don’t always interbreed. Sometimes one group just exterminates the other. Just ask the Dorset–oh wait you can’t. Because they’re all dead.

Physical variations in any given trait tend to occur gradually rather than abruptly over geographic areas.

The fact that “blue” and “green” shade into each other on the rainbow does not mean that blue and green do not exist.

And because physical traits are inherited independently of one another, knowing the range of one trait does not predict the presence of others. For example, skin color varies largely from light in the temperate areas in the north to dark in the tropical areas in the south; its intensity is not related to nose shape or hair texture.

It’s like the EDAR gene doesn’t exist:

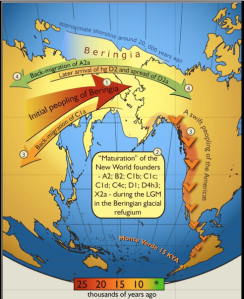

A derived G-allele point mutation (SNP) with pleiotropic effects in EDAR, 370A or rs3827760, found in most modern East Asians and Native Americans but not common in African or European populations, is thought to be one of the key genes responsible for a number of differences between these populations, including the thicker hair, more numerous sweat glands, smaller breasts, and dentition characteristic of East Asians.[7] …The 370A mutation arose in humans approximately 30,000 years ago, and now is found in 93% of Han Chinese and in the majority of people in nearby Asian populations. This mutation is also implicated in ear morphology differences and reduced chin protusion.[9]

Back to AAA:

Dark skin may be associated with frizzy or kinky hair or curly or wavy or straight hair, all of which are found among different indigenous peoples in tropical regions. These facts render any attempt to establish lines of division among biological populations both arbitrary and subjective.

So that’s why it’s so hard to distinguish an African from a Caribbean Indian, said no one ever.

So that’s why it’s so hard to distinguish an African from a Caribbean Indian, said no one ever.

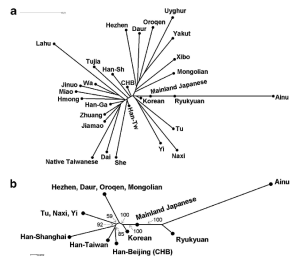

Genetically, of course, the divisions between the Big Three main human clades are quite plain.

…indeed, physical variations in the human species have no meaning except the social ones that humans put on them.

Unless you need a bone marrow or organ transplant. Then suddenly race matters a lot. Or if you’re trying to live in the Himalayas. Then you’d better hope you’ve got some genes Tibetans inherited from an ancient line of Denisovan hominins their ancestors bred with, present AFAIK nowhere else on Earth, that help them breathe up there.

Today scholars in many fields argue that “race” as it is understood in the United States of America was a social mechanism invented during the 18th century to refer to those populations brought together in colonial America: the English and other European settlers, the conquered Indian peoples, and those peoples of Africa brought in to provide slave labor.

People in the past did bad things, so all of their conceptual categories for understanding the world must have been made-up. And evil. There’s no way a European who just met an African and a Native American could have accidentally stumbled on a valid observation about human populations that were historically separated for a long time.

Anyway, the article goes on and on, littered with gems like:

During World War II, the Nazis under Adolf Hitler enjoined the expanded ideology of “race” and “racial” differences and took them to a logical end: the extermination of 11 million people of “inferior races” (e.g., Jews, Gypsies, Africans, homosexuals, and so forth) and other unspeakable brutalities of the Holocaust.

Hear that? If you think there are genetic variations between long-separated human groups, you are basically Hitler and the only logical conclusion is genocide. Because no one ever committed genocide before they invented the idea of race, obviously:

A 2010 study suggests that a group of Anasazi in the American Southwest were killed in a genocide that took place circa 800 CE.[15][16]

Raphael Lemkin, the coiner of the term ‘genocide’, referred to the 1209–1220 Albigensian Crusade ordered by Pope Innocent III against the heretical Cathar population of the French Languedoc region as “one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history”.[17]

Quoting Eric Margolis, Jones observes that in the 13th century the Mongol armies under Genghis Khan were genocidal killers [18] who were known to eradicate whole nations.[19] He ordered the extermination of the Tata Mongols, and all Kankalis males in Bukhara “taller than a wheel”[20] using a technique called measuring against the linchpin. In the end, half of the Mongol tribes were exterminated by Genghis Khan.[21] Rosanne Klass referred to the Mongols’ rule of Afghanistan as “genocide”.[22]

Similarly, the Turko-Mongol conqueror Tamerlane was known for his extreme brutality and his conquests were accompanied by genocidal massacres.[23] William Rubinstein wrote: “In Assyria (1393–4) – Tamerlane got around – he killed all the Christians he could find, including everyone in the, then, Christian city of Tikrit, thus virtually destroying Assyrian Church of the East. Impartially, however, Tamerlane also slaughtered Shi’ite Muslims, Jews and heathens.”[24] Christianity in Mesopotamia was hitherto largely confined to those Assyrian communities in the north who had survived the massacres.[25] Tamerlane also conducted large-scale massacres of Georgian and Armenian Christians, as well as of Arabs, Persians and Turks.[26]

Ancient Chinese texts record that General Ran Min ordered the extermination of the Wu Hu, especially the Jie people, during the Wei–Jie war in the fourth century AD. People with racial characteristics such as high-bridged noses and bushy beards were killed; in total, 200,000 were reportedly massacred.[27]

I’m stopping here. This stuff is politicized drek. It obviously is irrelevant to the vast majority of anthropology (what do I really care if the Inuit are part of the greater Asian clade when I’m just trying to record traditional folk songs?) But this drivel gets served up as the “educated opinions of scholars in the field” (notably, not the field of human genetics) to naive students and they don’t even realize how politically-based it is.

I don’t think anthropologists all need to agree with me about politics, but they should cultivate a healthy interest in science.